So, it has been one helluva month. Sorry for delay again, I wish I could say it due to the virus (though it certainly didn't help) but the honest truth that, deep down, I didn't want it to end. However, sometimes we just have to face the facts. But more on that later, let's finish this shall we?

My Top 25 films of the 2010s:

25. Homecoming: A Film By Beyoncé

Most concert films, even the acclaimed concerts are often about the spectacle. They are cinema of attractions that showcase a seemingly effortless musical performance and nothing else. Homecoming does that, and through sharp editing and well utilized behind the scenes footage, creates an exciting document of the pains and trials of making effortless spectacle seeming decidedly so as it plays before our eyes. The result is a spectacle that would have made the hearts of Jonathan Demme, Maya Angelou, and Stanley Donen explode.

24. The Handmaiden

Decadent, thrilling, erotic, and hilariously unashamed of it. A shocking tale of love, betrayal and sexual awakening filled with more twists than Hitchcock’s career, or a Kama Sutra coffee table book. It is also a cleverly subversive story of two women finding their autonomy and rebelling against a world ruled by a tyrannical male gaze with the skills forced upon them by said world. It is a lofty, provocative ambition that only filmmakers as absurd as Park Chan-Wook and his cast could find that perfect balance. The Handmaiden, the film that can have its cake and lick it too.

23. If Beale Street Could Talk

More will be discussed on him later, but has there been a more confident fresh filmmaker than Barry Jenkins this decade? From scene one, he beautifully balances its tone and ideas of two young souls (Kiki Layne and Stephan James, whom radiate like a star constellation) who hold on tightly to each other through the hurricane of injustice and systemic racism. Douglas Sirk and James Baldwin would have been proud.

22. The Babadook

In a decade horror where seemingly nobody believes that horror can be both character rich and horrifying, it is astounding to see something like The Babadook recapture the imagination and chill the spines of all walks of life. The titular monster, with foundations of German expressionist cinema, and folklore of both classic and the online variety, is one that never leaves the mind of the viewer; for as director Jennifer Kent understands, the best monsters represent what happens when humans submit to their worst thoughts.

21. The Irishman

How does one make a three-and-a-half-hour film seem almost too short? Give it to Thelma Schoonmaker, whose frenetic yet hypnotic use of Godard-esque cutting between Martin Scorsese’s biggest moments propels even his most unwieldy projects into masterclasses of epic crime cinema. The Irishman, perhaps, being his best epic yet. Starting like a cool throwback to Goodfellas, it slowly evolves into a tragic confession of a sinful and sorrowful man, trying to seek redemption that they know will never come. Time is unforgiving in that way.

20. Son of Saul

I remember seeing this with students, the shared trembling in the room as Saul—a Sonderkommando in Auschwitz—closes the gas chamber, and the silence afterwards. Like Come and See and Shoah, this film is one of most horrifically sobering portraits on the evils of fascism and the Holocaust. Don’t see it alone.

19. Meek’s Cutoff

Kelly Reichardt’s western takes the delirious existential tones of Monte Hellman’s The Shooting and amplifies it with a vivid eye for bleak pastoral nature, as well as a stronger emotional core. Slow cinema at its most gripping, it is a film that can find greater tension in the loading of a musket and depleted water canister than most blockbusters can with a world-ending weapon

18. Faces Places

If there is a filmmaker that one should aspire to be, it is Agnès Varda. Her oeuvre was an endless pulse of pure effervescent creativity, that only grew stronger with age. Faces Places, her penultimate film, is a documented testament to her effortless authority. It is lovely portrait of two artists finding simple pleasures in creating spontaneous art for a public in need of it and a passing of the torch from one of the keenest eyes of cinema. New wave is dead, long live the new wave.

17. Carol

The other great Sirk-ian melodrama, which honestly, more people should try imitating. More than just full-blown homage, Todd Haynes rediscovers the sophistication and delicate power of classic Douglas Sirk in this tale of female love and pleasure. Shot in crackling 16mm, this love story is shot with the kind warmth and formal elegance that would be impossible in any other mode. Besides, why settle for shaky neo-realism when one can have Rooney Mara in a Christmas hat?

16. Grand Budapest Hotel

The greatest dollhouse in a career full of them. This Wes Anderson comedy is an intricate, nostalgic, and delightfully plotted ride full of thievery, backstabbings, and chases that will leave one grinning like a fool the moment it ends, and in tears the day after.

15. Phantom Thread

From one Anderson to another. To view Paul Thomas Anderson’s story of a tailor falling for a foreign waitress, for the first time, is to second guess everything one expects from dramatic storytelling. Is this a ghost story? A confession to a murder? A screwed-up romantic comedy? All of these things? All that is clear by the end is that this sumptuously crafted duel of wits is utterly addictive. Vicki Krieps and Daniel Day-Lewis are more than match for each other as two lovers that sharply prod each other into submission. Every glance, glare, and spat feels like a knife slowly peeling into their being. This is a singularly bitter, droll, and venomous tale will make one squirm as they watch it, again, and again.

14. Inside Llewyn Davis

See Llewyn Davis, a washed-up folk singer who tries and fails so hard at life that one wonders if he should rename himself Charlie Brown. Like much of the Coen Brothers’ films, this one is brutally sardonic, yet underneath reveals a heartbreaking character study of a man grieving. This film is a beautifully somber elegy of not only of a man whose best days are behind him, but of an austere yet well-intended musical movement that dissolved into the veneers of pop. Good grief, indeed.

13. Under the Skin

A running gag in film school (sorry Mom and Dad) is that someone will call any film with a hint of symmetry and steady-cam shot: “Kubrick-ian.” As if cinematic sterility is all there is to Stanley Kubrick. Johnathan Glazer shows that he gets it with this story of an extra-terrestrial (played by Scarlet Johansson) luring men to their doom. Under the Skin has the chilling atmosphere, extraordinarily bold imagery and smooth patient pace of Kubrick at his most unnerving. However, Under the Skin pushes beyond unease into unknown territories. The film slowly reveals one riddle after another on the like of gender, identity, masculinity, and violence, that culminates in an unnerving climax makes one question the worth of humanity as a whole. It is a film that glares back at the viewer and dares them to blink. Now that is “Kubrick-ian.”

12. Parasite

A tight Hitchcockian thriller with the tragically human spirit of Jean Renoir. A blockbuster that tackles the uncertainy, oppression, micro-aggressions brought upon by late-stage capitalism with sharp satire that never pulls back and never stops moving. It will make one laugh, cry, and grip their chair as these folks fight for air in this torrential flood of a film.

11. The Duke of Burgundy

A film so sensual, its opening title sequence credits a fragrance. The Duke of Burgundy is a film that breathes 70s exploitation, with its story of two women (Sidse Babett Knudsen and Chiara D'Anna) exploring their romantic relationship through BDSM, yet it is never shackled by these influences. The plot heightened yet refined tale that would rather cut around nudity and examine the rituals and patterns of love after “happily ever after.” Through the acts of measuring furniture, washing clothes, and barking commands, the film provides a window into a complex and engrossing story of two women struggling to understand each other’s emotional needs as well as carnal ones as they age. The film is also unafraid to convey its mood beyond the fundamentals of montage but in lighting and sound that verge on the avant-garde. Each moment is progressively more dreamlike without ever feeling indulgent, but only immersing us further into the psyche of the kind of love that is too complex for words. After a while, one can almost smell the fragrance.

10. Toni Erdmann

Here we are in the final stretch, after pushing through forty entries of gushing superlatives, it feels exhausting to try gushing even more. If I felt more like a gusher, I’d be filled with fruit syrup and sold in the candy isle. If that joke hurts your brain, well, have I got the film for you! Directed by Maren Ade, Toni Erdmann is a film I admired back in 2016, which in hindsight, changed my sense of humor beyond repair. It is a crass yet sharp German comedy about a retired dad trying to reconnect with his business savvy daughter in the only way he knows how: by being such a god damn dad. This is nearly three hours of dad jokes, awkward quips, and pure embarrassment that would even make Michael Scott jump out a window. It makes one wonder how anyone can put up with dads, which is also part of the sad power that Maren Ade brings to this film. It is a study on the emotional toll of parents trying to connect with their adult children after they leave the family home to work in a world that moves faster than ever. It is painful and warm in all the right ways.

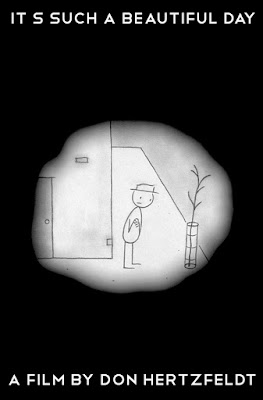

9. It’s Such a Beautiful Day/World of Tomorrow

To imagine that one of the most heartbreaking portraits on facing death and mortality would be an hour-long, glibly narratted stick figure animated film from Don Hertzfeldt—the man who gave the world such quotes like “My spoon is too biiig.” Still incomprehensible. To imagine that this animation wunderkind would match that power with the twenty minutes of bittersweet life affirming sci-fi that is World of Tomorrow. Miraculous.

8. The Rider

The most beautiful and introspective western of the decade. Chloe Zhao’s careful eye for nuance not only allows for some of the most transporting shots of the Midwest this side of Days of Heaven but also to delicately craft one of the most crushing tales of an American dream poisoned by toxic masculinity without failing to find empathy or hope at its core. The story Brady Blackburn is one that feels painfully relatable and familiar as the film showcases him falling behind in an evolving world after horrifically losing his shot at the rodeo, yet it almost feels so mythical. To see Brady rest joyride on a horse is a moment that is both inspiring and heartbreaking, knowing that even this respite is slowly killing him. Part documentary, part modern folk tale, it is an elegiac film about how one’s dreams can just as easily imprison their souls as well as give one purpose.

7. Dawson City: Frozen Time

Speaking of dreams, if there was one film that made me rethink my own, it was Dawson City: Frozen Time. In a mesmerizing collage of photographs and decayed films strips discovered in the titular Alaskan town, this film creates an expansive, somber, and nostalgic seance of a country finding itself only to forget its roots. Every photograph and filmstrip seem to breathe its final breath as the film progresses further to the present. A vivid reminder of how cruelly people can mistreat art but also of the broken dreams that built the USA. It is cinematic archeology told with soul churning poetry.

6. The Act of Killing/The Look of Silence

It was a rich decade for documentaries, and with the boom of streaming services simply amplified the genre as mainstream content, for better or worse. For every compelling documentary with something to say, it seems like there is seems to be a dozen filmmakers exploiting a tragic death, under the pretense of finding “the truth” when it is just snuff cinema made glossy with sardine oil. What makes The Act of Killing and The Look of Silence—sibling films about the 1965 mass killings in Indonesia—is that not only do they bravely interrogate its subjects without minimizing the gravity of their crimes, but they also interrogate the idea of truth in cinema. The Act of Killing is a shocking view not just because it examines a selection political killers decades after they have won, but they are under the impression that the filmmakers there to portray their glory. As Joshua Oppenheimer and his anonymous crew play along, they reveal how entire generations are made to normalize evil through layers of systemic oppression, fear, and propaganda most of all. The Look of Silence (filmed by the same crew) conversely follows an optometrist as he questions such killers about the murder of his brother. These films interrogate their subjects with an effortless bravery that is all too rare in both cinema and journalism today. If there was a pair of documentaries that truly mattered in this decade—documentaries that can make one grasp the difference between showing and revealing—it would be these two films.

5. Hard to Be a God

What a putrid, harrowing, and epic film. There are medieval epics where a knight with a rose in hand rescues a damsel from an evil king; there are medieval epics that delve in the political intrigue and gritty violence; then there is Hard to Be a God, a film that begins with peasants literally smearing shit on each other. Anchored with through the perspective of a modern man observing a planet fixed in a self-perpetuating Dark Age, this film is an intoxicatingly pungent cavalcade of medieval squalor, as well as an unwaveringly horrific allegory on the folly of anti-intellectualism on a global scale. This is not Game of Thrones, this is director Aleksei German reinterpreting Bosch’s visions of hell as a cackling cinematic abyss. For the longest time I thought this film was cursed. Granted, if one watched Hard to Be a God on New Year’s Eve of 2015, the following five year could make one imagine they saw a prophecy, in hindsight. All that said, I keep thinking about this film. As one develops a tolerance for grime, German’s almost instinctual eye for epic imagery, humor darker than vantablack, and tarnished beauty in this mad world becomes clear. It is the last film Aleksei German ever made—having died during the post-production phase—and with it he teaches one how to stare into the abyss and laugh at it. For that, I thank him.

4. Holy Motors

How does one even begin to describe Leos Carax’s Holy Motors?

Is this a provocative surrealist art-house poem? A rambling mess of stray thoughts? A somber and beloved tribute to both Carax’s life partner, Yekaterina Golubeva, and to the cinema industry as we know it? An avant-garde rallying cry towards the cool embrace of digital film? Maybe it is a little bit of everything. Either way… holy moly.

[Editor’s note: I would like to apologize for ending a paragraph with holy moly, of all things. At a certain point—when a film evokes so many complex emotions and thoughts on the likes of death, the future of cinema, and conformity all at once through cinematic language alone—one can only process it all with grade school phrases. Please do not let this writer’s shortcomings dissuade from seeing one of the most indescribably brilliant, weird, and exciting films of the last decade]

3. Cameraperson

If there was something that stuck with me in film school (again, sorry Mom and Dad), it is a quote from Dziga Vertoz: “I’m an eye. A mechanical eye. I, the machine, show you a world the way only I can see it... My way leads towards the creation of a fresh perception of the world. Thus I explain in a new way the world unknown to you.” To paraphrase, what Vertov describes is the fundamental power and struggles of the cinematographer. The camera is an extension of the one wielding it; therefore, a film is in mercy of their perspective. It is a righteous duty of the cinematographer to view the world with as honest an eye as one can. Kirsten Johnson’s Cameraperson is a modern, beautiful constructed, and personal tone poem about a career-long pursuit for that eye.

Throughout the film, one is intimately aware of Johnson’s presence behind the camera as she adjusts the focus, removes grass blocking her vision, and asking questions to her subjects, which is par for the course. Having worked as a cinematographer for dozens of documentaries, many of which are eluded in this film, this is what of the job entails. However, more than just A Woman with a Movie Camera, Johnson also provides glimpses into her personal life, family videos of her twins, scrapped personal works, and recordings of her ailing mother. Through montage alone and little to no flourish, these images become both a kaleidoscopic diary her of career and an affirming document of the chaotic beauty of life on Earth of the 21st Century. The audience immerses into her eye, allowing them to see the complex beauty of the world through the raw images she has witnessed in a life full of hard work, tragedy, and warm memories. In this sense, Cameraperson is ultimately the best kind of film about filmmaking.

2. Moonlight

The last ten years saw a new wave of American cinema. From Certain Women to The Fits to The Florida Project to The Rider these are films that used cinematic language to its fullest in order to create amplified, poetic, and empathetic realism of modern America life. This was a tremendous wave of new voices telling stories of people rarely heard in decade before. However, they seem like ripples in the wake of Moonlight; a film so miraculous in its execution, not even The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences could believe it.

A coming of age story told in three acts, director Barry Jenkins proved to be one of the most exciting visual dramatists of his generation with each progressing act. He combines the spontaneity of Francois Truffaut, the smoldering intensity of Spike Lee, and the cool majesty of Wong Kar-wai in a matter that is not only looks effortless but transcends these influences with his ability to find the universal within the specific. One may not relate of Chiron—an African American kid coming to terms with his sexuality—personally but one can empathize with the anxiety of discovering their desires, the pain internalized from years of being bullied, and the quiet ecstasy of feeling loved just by looking at his face. It is a film that gently holds the viewer by the wrist and takes them into the psyche of one whose voice often goes unheard and make them feel every emotion with uncanny synergy. What Barry Jenkins pulled off with this film is pure magic. There may be more elaborate and in-your-face filmmakers out there, but none have such gentle, elegant, formal technique, yet keen sense of the present as Barry Jenkins. He is possibly the best American filmmaker working today.

1. Mad Max: Fury Road

This is it, the film that shook the theater. To call Mad Max: Fury Road lightning in a bottle would be selling the film short. People were ready to write this film off ever since it was greenlit, including myself, but then people saw it and my god. Experiencing this film for the first time was like witnessing a miracle in how much it defied all expectations. George Miller took over a hundred years of blockbuster cinema wisdom and purged it all into a singular masterwork of action cinema. It has been discussed to death that the chase fueled plot being a clear riff on Buster Keaton’s The General, but one can see the scorching grit of Sergio Leone, the grandness of David Lean, and Jim Henson’s knack for grimy high fantasy. However, this is ultimately an experience of George Miller’s making. Mad Max: Fury Road is a spectacle of the heavy metal Ozploitation action that Miller defined back in the 80s but amplified to a magnitude that nobody expected, and as of now, nobody knows how to replicate. Like when Eric Clapton saw Jimi Hendrix play live for the first time, every filmmaker worth a damn saw this film and thought, “what am I going to do now?”

Earth shattering action aside, what puts this film over the top is that through deceptively simple storytelling and a razor-sharp sense of cinematic language, and time, Mad Max: Fury Road one of the most prescient and righteous films of the decades. The film calls out misogyny, climate change denial, toxic masculinity, and fascism with Furiosa and her crew of badass women angrily asking, “who killed the world?!” This is as much a tale of women fighting for their autonomy in world that cannot even spell it as it is about Max finding his self-worth after losing it. Are the themes messy? Yes, but what isn’t these days? What makes the tales of Max and Furiosa so inspiring and compelling that they remind the viewer that they are not alone. Even as it seems like the world is crushing their backs, someone, even a stranger, can help one push back. It is sentimental, but it is a sentiment that is as honest as cinema can be. There might not be another action film like Mad Max: Fury Road, not just because of its pure sense of spectacle, but that it is the only piece of spectacle that matters this century. It mattered in 2015, it matters today, and at this rate it will in the future. Not bad, for a two-hour chase sequence.

So, that's that. Now for the serious news, so as some of you may know I'm working on my Master's degree for Library and Information Sciences. The program is going great but the workload is progressively getting larger, more intensive and since it is online exclusive, not even a literal plague could stop me. It got to a certain point where it just became impossible both write extensively about movies and also find time to even watch them, which is an absurd way to live. So after a painful amount of contemplating, rather drag this blog down with more random unannounced delays, I have decided to put this blog on an indefinite hiatus. I might be gone for a couple years, it might be permanent (I hope not, though), either way, it'll be a long time before I update this blog. Nevertheless, you can still find me on Letterboxd, where be writing briefer and more informal reviews.

Finally, thank you for everyone who has helped out with this blog the last ten years. It was a more solid than I expected and your help and appreciation has help me grow as a writer. Hopefully I can make good use of these typing fingers somewhere in the future.

"Where must we go... we who wander this Wasteland to search for our better selves?"

-The First History of Man

No comments:

Post a Comment